The First Anniversary of "The Fourteenth of September:" The 50th Anniversary of Everything That’s In It 🎂

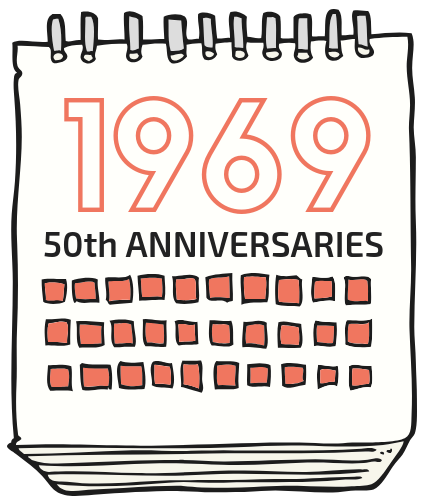

/It’s been a year since the publication of my debut novel, The Fourteenth of September, and I can’t believe it either. To answer so many of your questions, yes, it has done well (outperforming the average independent book, I’m told) and continues to be of interest. It’s fulfilled all my hopes and dreams, and I’m humbly grateful for the wonderful year I’ve had due to the support of many of you. I intend to continue the ride as long as it lasts, however wild. This last quarter of 2019 alone is filled with the fiftieth anniversaries of so many of the seminal events of the time that are dramatized in the novel: the Chicago Conspiracy Trial, the first Moratorium Against the War, the March on Washington, the first Draft Lottery. Their commemoration shows us how the decades can seem very long ago, and yet as short as a heartbeat, with in-your-face reverberations today.

To be honest, everyone is right when they say publication is not for sissies. Though incredibly affirming and rewarding, it’s also been, in the favorite words of the colorful Joe Dragonette, “three yards and a cloud of dust.” To my surprise, the part that gets so many writers, the marketing, was often overwhelming even to my PR veteran self. But the biggest challenge was always that my topic was so fraught on so many levels. Me, being me, I just couldn’t begin with a simple starter novel with a few characters and a feel-good climax. And that made the hill I had to climb pretty high, though a few major things did finally break in my favor.

Following is top-line some of what I learned during the year of the launch of The Fourteenth of September.

Vietnam is No Longer the Voldemort of Wars

read the first chapter which takes place September 14, 1969

Timing is everything, and there was a long period when I thought I’d totally blown mine for publication. The book took thirteen years to write (and that’s once I actually put fingers to computer) and I suffered through many questions about why I was writing about Vietnam—a subject no one cared about, I was told. It was the Voldemort of wars, as one of my book-launch salon participants put it: We lost, there were atrocities, and we treated our vets badly. Nothing anyone wants to revisit. And besides, it’s the past, not relevant for today. Why waste your time?

Fortunately,my au contraire moment was created by Ken Burns (The Vietnam War PBS), Steven Spielberg (The Post), the writers of This is Us, and other popular culture curators who reminded us at the fifty-year point after the war that it was time to look back, learn, and even—be still my heart—be entertained. In addition, with the interest in women’s issues and diversity, there was increased openness to new points of view. As a result, once I published, I became part of the zeitgeist. In fact, the New York Times recently pointed out that three of the current bestselling novels are also at least partially set in 1969, with Vietnam themes or plot points: Summer of ’69, Mrs. Everything, and Chances Are…, the latter of which is actually about three college buddies whose lottery numbers pretty much determined their lives.

Unfortunately, world events have lined up to show that if not examined, history will always repeat itself. So alas, counterintuitively, what’s uncomfortable for the country makes The Fourteenth of September more relevant than ever. It was chillingly familiar when Pete Buttigieg reminded us in the second Democratic Debate that wars are “very easy to start and very hard to end.” He was referring to Afghanistan, but the echo to Vietnam, that limped on five years after Kent State turned the country firmly against the war, was loud and clear.

It’s time to embrace the subject of the Vietnam War as we would any in history. Check out the article I wrote about this for Independent Publisher: “Five Reasons Why It’s Okay to Write about Vietnam Today.”

Vietnam Is Still a Tough Subject, but Not One to Shy Away From

—People actually do want to talk about Vietnam, given the opportunity. In over thirty events during the past year, I’d say, men, in general, are eager to share their particular stories—how they did or did not get out of the draft, the near-miss life-saving efforts of helpful doctors, the miracles of lost or destroyed draft documents. They also remember where they were on Lottery Night—in a bar, huddled around a TV in a dorm, in a pool hall—afraid to listen, feeling powerless, their destiny out of their hands. They shared stories personal and painful as if they’d been just waiting for an opening. They talked about what got them through—tales and talismans. The real-life model for the character of Wizard in my novel pulled the remnants of his draft card out of his wallet and reassembled them on a countertop to show me they never left him.

—Women are mixed. They usually don’t feel they have stories of their own and start with those of their men: fathers, uncles, husbands, sons, students, relatives relegated to the dark and never talked about. Once they “claim” their experiences, their stories are as compelling. One woman told me she’ll never forget picking up the paper on the front porch the morning after the second draft lottery to read that if she’d been one of her five brothers instead of a girl, she, too, would have the lowest lottery number and been off to Vietnam. Many were apologetic—they’d been focused on raising kids, or writing papers at college amid the chaos, or just keeping their heads down and their lives moving forward as the world was blowing up. One of the most telling comments was from a seventy-nine-year-old woman in Wisconsin who came up to me after a book club. “I got married young and didn’t go to college,” she said as if I’d judge. “My husband was on the road as a salesmen five days a week and I was overwhelmed raising three kids. I thought all the protesters were entitled rich kids, causing trouble.” She thanked me for showing her their perspective as she revised her own.

—Young people are very curious. Not so much Millennials, who find it hard to relate, but Xers and younger who say they want to hear more about a subject no one talks about or teaches. They haven’t heard about the Lottery and have a hard time believing that it happened as it did—like a game show on television. They instinctively feel that Vietnam is an important part of their history and that others have decided it’s not to be shared. They want to understand why.

It Still Hurts. Time Helps but Doesn’t Heal.

—Vets are still angry. Some violently so. Several of the comments to my Facebook Ads were pretty hot, by vets viscerally reacting to nothing more than the photo of a protest sign and the name of a female author. I tried to engage with a few to tell them the book wasn’t anti-vet, and one did respond, thanking me. But I had to pull back on my audience target, realizing I was pouring kerosene on a wound that was still open.

—Vets are still profoundly hurt about how the war was conducted and how they were treated. Callers-in on radio shows spoke primarily about that. They were anxious to share. I was willing to listen. My attempts to donate some proceeds to The Wall or Vietnam Vet organizations were mysteriously rebuffed. One sympathetic man finally told me it was too much of a reach. The Vietnam Vets were focused on supporting vets of subsequent wars, so they wouldn’t be treated poorly like they had been. When I brought book copies as giveaways to my high school reunion, I had to start by saying the book was anti-war for that war at that time—not anti-vet.

When my publicist emailed with a link to a review of The Fourteenth of September in The Veteran I held my breath. To her, this had been an obvious media target, but I knew better. Now, I’m more proud of this than any other I’ve received:

Few books have taken the time—and space—to examine so thoroughly the collegiate antiwar movement in small-town America. The story held my interest and reminded me of what was going on in Pullman, Washington, around the same time. The tone rang true in every line.

I was interested in the impact that the draft lottery and its rippling effects had on a generation heavily influenced by the chance uncertainty the lottery had on hundreds of thousands of young people. I had barely paid attention to the lottery because I was one of the young men drafted before it was instituted.

This novel opened my eyes to issues that my thick skin and my age had protected me from. We are admonished to read this book and weep, and I actually did shed a tear or two of sympathy.

If you’re like me, after you read this well-written novel, it will be difficult to put it out of your mind.

We Can Still Be Surprised by the Past

In one of my book-launch salons, I met Pam Tarr, daughter of General Curtis Tarr, who was the much-maligned “inventor” of the modern draft lottery. I didn’t know her history but had been warned she’d attend and I should be prepared for tough questioning. That didn’t happen. She was open and sympathetic to the story of characters protesting what had been her father’s program. Later, she told me about how the objective had been laudable—to come up with a uniform, fair program versus the uneven and “bribable” local draft boards than in place. Her father and her family had been vilified and taunted. She told a story of how President Nixon had urged her to be brave. Her best friends were the daughters of Ehrlichman and Haldeman. It had been a hard adolescence and she felt it hadn’t been fair to her family. And, of course, she was right. War does so much unseen damage to so many unappreciated victims. Many of the overlooked are women and girls. I’m hoping she and I will be willing to work together on this story at some point.

Historical Fiction Is a Pathway to Understanding

I’ve always felt that we learn our history through facts and nonfiction, but we understand our history through narrative—where we can actually feel ourselves in the shoes of a character we can relate to and wonder what we would have done. Then, we can begin to know what it was like to weigh the stakes and dangers against the valor and objective, and consider what it was like to live in another time: to make a fateful decision in the narrow vision of a single person’s experience of the past without benefit of the panoramic reevaluation of the present.

Historical fiction typically takes place at least fifty years in the past. The Vietnam War, as a subject, is now just squeezing into that category by its chin hairs. It’s complicated. Living people bring the lens of their authentic, yet specific involvement to the story. Some feel that unless they had their own experience of Vietnam this story wouldn’t be relevant. This story is only for a Boomer audience of a specific age, in this micro-targeted world. Right?

And yet, we openly welcome stories of topics of which we have no living experience—the French Resistance, German prison camps, home-front US—in stories like The Lilac Girls, All the Light We Cannot See, The Beantown Girls, The Lost Girls of Paris. Members of book clubs press novels on me about other wars they see as parallel and relevant. People send books, poems: Pandora’s box has been opened. Vietnam is as relevant as today, as nostalgic and fascinating as the yesterday of World War II and all the history that’s gone before. The stories the War has to tell are compelling, gut-wrenching, instructive, revelatory, and

. . . entertaining. The Fourteenth of September, for example, is full of the sex, drugs, and rock and roll of the time. It’s impossible to write about 1969-1970 without being a bit uncomfortable, yes, but also with singing and celebrating.

It’s time to open ourselves to the narrative. Over the next few months, as we commemorate the pivotal events of fifty years ago, this blog will utilize The Fourteenth of September as a lens to allow you to experience this chaotic and prescient time from the perspective of the nineteen-year-old you once have been, will be or still are. And, to consider what you would have done then, and may yet need to do, again in the near future.